Test for Echo

Visual Resonance and Trans-Corporeality in Contemporary Nordic Photography & Art

It’s Springtime in Prague, and with the blooming of lilacs comes a renewed eagerness for lively art fairs, exhibitions, and music. I found such novel delights this week in the work of Karolina Nocoń, a Polish artist based in Norway who specializes in portrait and landscape photography.

At a wonderfully intimate exhibition titled Echoes, Nocoń presented a sample of her haunting photography. Not content to leave visual mediums as the only food-for-thought that evening, attendees were later serenaded with a performance by FRUM, the musical project of Faroese artist, Jenný Kragesteen.

Much to my retrospective annoyance, I was unfamiliar with Nocoń’s art prior to this exhibition—a shame, since much of her artistic rationale intersects heavily with my own academic research. Balancing questions of the human and non-human throughout her visual medium, Nocoń invites us to question the permeability of presupposed binaries—not only between the human and the non-human, but also between the visual and the auditory. One is struck, indeed, by her choice to name the exhibit Echoes, a title which evokes the aural over the ocular.

Nocoń is one step ahead of us, anticipating our inevitable question and providing an answer:1

There is a kind of seeing that begins with listening. Though these photographs are born of light and form, their true subject lies in the act of attunement—to water and wind to the groan of ice, the hush of snow, the invisible rhythm of growth and decay. Something unfolds here that is at once ancient and fleeting: a moment suspended between presence and vanishing. In listening to the natural world, we begin to dissolve into it. We do not merely observe; we are observed. The boundary softens. We become the vibration, the breath between waves, the spaces between sounds. And what if the questions we carry into the forest, the mountain, the shore—have already been answered? What if the world outside is not outside at all, but a chamber that responds to our own voice, changed just enough that we can finally hear it? These images do not explain. They return. They reflect. They ask again.

The reflexivity between the cultural and the natural, the human and the environmental, which Nocoń explores within her photography, gestures towards larger philosophical questions arising in the wake of ecocide and climate disaster. Her photography speaks (with all that verb’s clever associations) to the trans-corporeality of an embodied universe.2

Drawing on Stacy Alaimo’s definition, trans-corporeality highlights the interconnectedness and interdependence of human bodies with the material world—especially the environment, animals, chemicals, and technologies. As a methodology, it challenges the notion of the human body as a discrete, bounded entity by foregrounding the constant exchanges between bodies and their surroundings, whether biological, ecological, and socio-political.

This is precisely the interconnectedness demonstrated in Nocoń’s untitled piece from her May series. Featuring a human model lying amid moss and leaves, the status of the human as subject (agential, centralized, gazing) is challenged through the intentional obscuring of the model’s face. Stripped of personal identity, her facial features are replaced with a strategically-sized strip of lichen-covered bark. The human, in this instance, has become the vehicle through which the identity of nature is presented to the viewer. Yet the human is not fully dissolved: the model has not been entirely relegated to the status of object (passive, decentralized, gazed upon). Not fully sublimated, yet not entirely focused, the human body works in tandem with natural features to create a composite entity as unique in its identity as a human countenance—or the face of a mountain.

While surface-level comparisons might be drawn to René Magritte’s Le fils de l'homme (1964), the effect produced in Nocoń’s photography is entirely different. It invites us to question where the boundary between the human ends and the natural begins. The model of the photograph remains firmly present in this piece, even as her face is obscured. Her body, clothed in soft, earth-toned fabric, evokes a bed of soil or tree bark—textures upon which lichen and moss might naturally thrive. One detail in particular catches the eye: green-dye streaks the model’s brunette hair. Though this color might typically suggest artificiality, here it deepens the ambiguity, further dissolving the divide between figure and backdrop. The green foliage entangled with her hair appears as integral to the dyed strands as to the surrounding wilderness.

The resonance in this piece is visual, but it evokes the type of reflexivity one might expect of an auditory echo. One may ask, why use a sonic metaphor to demonstrate visual reflexivity? Why not, for example, a mirror? I asked myself the same question while perusing Nocoń’s exhibition. There is a productive tension in considering reflexivity within a visual medium like photography. Yet I am convinced the metaphor of the mirror does not suit her work. Nocoń’s photography does not reproduce the heterotopia of Foucault’s mirror—where presence is mediated through inversion, allowing the subject to locate themselves through confrontation with an “elsewhere.” Instead, her work does not invert or displace; it enmeshes. It neither centers the ego nor simply reflects a social world.3

Despite the artist’s own claim that, “these images do not explain. They return. They reflect. They ask again,” I would propose something slightly different is happening. These images are not reflections but composites—harmonies that rebind the human and the natural into a shared continuum, rather than isolating them as separate realms. There is music made visual here: a quiet chorus affirming the human as one thing among many, not a detached observer gazing into a reflective surface. The echoes to which Nocoń gestures do return—but they return transformed, as part of a dialogue rather than a soliloquy.

The Fleeting Impermanence of Sound & Flesh

Themes of cyclicality and fading echo through these photographs. Like sound reverberating through space, there is repetition—distorted by the landscape its vibrations encounter—and diminishment. As the human speaks into the vastness of nature, extending the body into a universe in which it comprises only a small part, we are made aware of its impermanence: like wind across water, our echo fades and mingles with the tones of other natural entities.

This concept finds further manifestation in another untitled piece from the May series, in which a distorted, blurry image of a human strides across the rocky shore of a fjord. The shoreline, water, and towering mountain behind this figure are sharply in focus.

They are unwavering. Unchanging.

The imagery is clear: there is no ego amid this ancient landscape that has seen many such humans blur and fade as quickly as they emerged. As Nocoń herself tells us: “Something unfolds here that is at once ancient and fleeting: a moment suspended between presence and vanishing.” One senses that the blurred figure is merely one among a continuum of such figures passing along this shoreline. The impression is not that they are external to the landscape, but that the presence of nameless humanity is as central to its being as the titanous presence of the mountains. The blurring of the human subject (which generates a sense of motion) places the generalized human body within the conceptual framework of life itself. In Old Icelandic, að kvika (to move, to stir) and kvika (the quick, life, yeast) coalesce the ideas of motion and vitality. The subject is not merely vanishing—it is quickened.

Here again we find trans-corporeality. By choosing Scandinavia as her subject, Nocoń aligns herself, whether deliberately or not, with the eco-narratives latent within Nordic mythology. The thirteenth-century Icelandic mythographer, Snorri Sturluson records in Gylfaginning that the cosmos was formed from the body of a primordial giant named Ymir:

[The gods] killed the giant Ymir… and made from him the earth, out of his blood the sea and the lakes. The earth was made from the flesh, and the rocks of the bones, they made the stones and rubble of the teeth and the molars and from those bones, which were broken.4

As I have discussed elsewhere, the Norse cosmogonic myth is inherently trans-corporeal.5 The universe of Norse myth is an explicitly corporeal one—environment and anthropomorphic form are the same entity. Rather than bifurcating or sublimating human and environmental, myth places both within a flat ontology. As Bruce Holsinger observes:

Unlike philosophy, though, mythography has the virtue of placing the human (and everything else) at the mercy of numerous external forces over which we have little or no control even while enmeshing us within a supernatural world of objects that confronts us with the limits of our analytic ingenuity and interpretive skills.6

In choosing landscapes as subject, Nocoń invites interpretation through the lens of Scandinavian narratives—literary and ecological. If culture and nature exist along a continuum, then the landscapes she depicts echo back not only individual human voices, but the prolonged reverberations of humanity across time. Her work is trans-corporeal not only because it composites human and environmental, but because it participates in myth, drawing the human into patterns of cosmic rhythm rather than setting us outside them.

Scandinavian Landscapes and the Embodied Universe

The theme of trans-corporeality resonates beyond Nocoń’s photography and finds compelling expression in recent Scandinavian art. One artist whose work stands out in this regard is Marie Sophie Besson (Marie & Giboulèe Art), whose portfolio has captivated me both intellectually and emotionally. I had the good fortune of meeting Besson at a conference on medieval Icelandic literature last month, and can say without hesitation that the depth of her artistic skill is matched by the breadth of her literary insight.

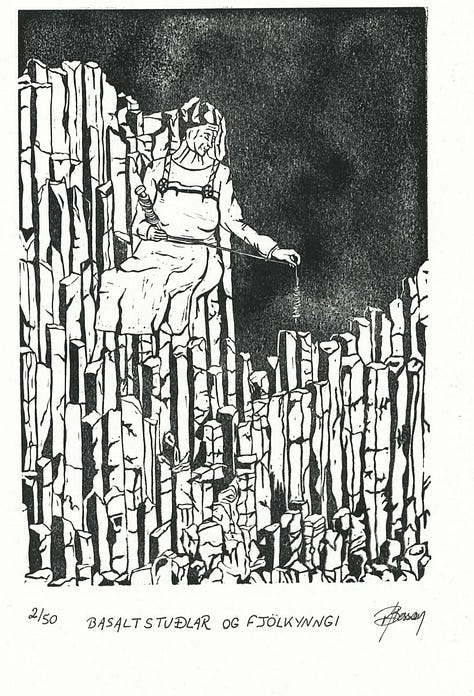

Besson, like Nocoń, engages deeply with the intersection of humanity and the natural world. Drawing on Iceland’s landscapes as her primary inspiration, her recent linocut pieces—Basaltstular og fjölkynngi and HEIMA—use the island’s ubiquitous basalt formations as visual and conceptual material to explore human embodiment, though to distinct ends. In Basaltstular og fjölkynngi, an elderly woman sits spinning wool. Her form is continuous with the basalt columns upon which she rests—simultaneously enthroned by and constituted of them. Yet the act she performs is not merely domestic. As the title suggests, she is practicing fjölkynngi (magic/sorcery). Like the mythological nornir who spin the fates of men, this basalt-woman engages in a magical act of weaving.

Does she spin fate? Perhaps.

But more than fate, what she weaves seems to be the connective tissue between body and earth. Besson’s medium reinforces her message: by choosing linocut, she quite literally carves the image of this magical woman from a metaphorical basalt, transforming the material process itself into a meditation on environmental entanglement. The artwork becomes not just representation but inscription—an embodied act that blurs the line between the organic and the artistic.

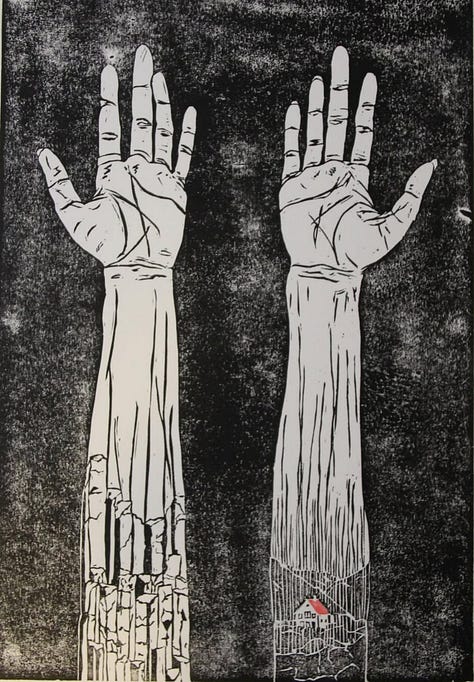

This interplay between medium and meaning is again central in HEIMA. Here, Besson presents two outstretched arms—ambiguous in identity, perhaps belonging to the artist, the viewer, or humanity at large—each marked by long, vertical cuts. The scars, suggestive of self-inflicted wounds, double as inscriptions. As the cuts extend downward, they shift in form: on the left, they become basalt columns; on the right, streaks of rain falling on a rooftop. Which side is heim—home? The visual ambiguity refuses a simple answer. Instead, Besson proposes that home is constituted through both cultural and natural inscription. The body bears the marks of both environments; neither is exclusive, and both are formative.

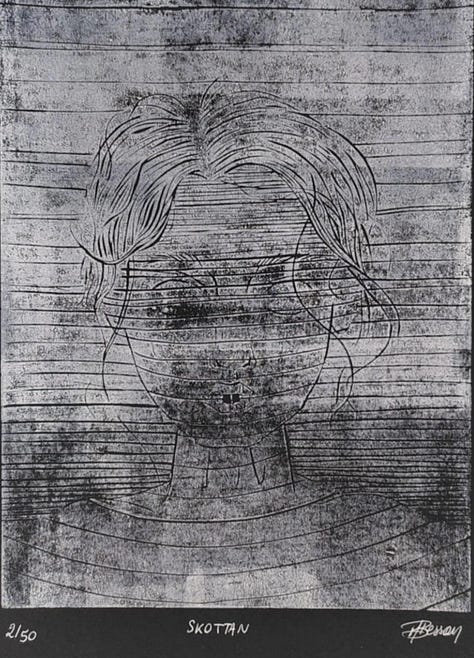

While I hesitate to call this trans-corporeal aesthetic a trend, there is clearly a growing concern among Scandinavian artists with the dissolution of the human-nature divide, especially in the wake of accelerating climate catastrophe. Nocoń and Besson offer distinct but complementary responses to this cultural moment. Besson, in particular, seems to focus not on echo but on inscription: the ways in which material, form, and technique impress themselves upon the human figure. A compelling example is her piece Skottan, where a human face carved in wood is visually disrupted by the grain of the material.7 The horizontal lines of the carving merge with the horizontal striations of the wood, blurring the figure’s features until only the vertical lines—those running perpendicular to the grain—remain legible.

For those familiar with medieval Scandinavian culture, the visual metaphor is striking. The runic alphabet, which avoids horizontal strokes to remain legible when carved into wood, operates under similar constraints. Skottan thus becomes a meditation on legibility, identity, and the conditions of visibility: a feminine face emerges only through vertical inscription, its features shaped and obscured by the medium that contains it. It is a powerful fusion of form and function, art and semiotics.

Taken together, the works of Karolina Nocoń and Marie Sophie Besson form a compelling conversation about the limits of the human body, the permeability of self, and the role of art in navigating ecological collapse. These artists do not merely depict the natural world—they enact its entwinement with human experience through material choices, aesthetic distortions, and mythological allusions. Through echo and inscription, obfuscation and exposure, their art challenges us to reconsider what it means to be human in a cultural and political moment when traditional binaries are increasingly obscured. What they accomplish is not a confused and dissonant noise, but rather a clear vision of reconnected harmony: art as ecology/ecology as art.

This text is taken directly from the artist’s rationale, which was displayed alongside her photography at the Echo exhibition (Prague, May 14, 2025).

On trans-corporeality, see the work of Stacy Alaimo. Especially, Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010); “Trans-Corporeal Feminisms and the Ethical Space of Nature,” in Material Feminisms, ed. Stacy Alaimo and Susan Hekman (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2008), 237–264.

Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias,” trans. by Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16, no. 1 (Spring 1986): 22–27. Originally presented as a lecture in 1967.

My own translation; “Synir Bors drápu Ymi jǫtun […] ok gerðu af honum jǫrðina, af blóði hans sæinn ok vǫtnin. Jǫrðin var gǫr af holdinu en bjǫrgin af beinunum, grjót ok urðir gerðu þeir af tǫnnum ok jǫxlum ok af þeim beinum er brotin váru,” (Edda: Prologue and Gylfaginning, ed. Faulkes 2005, 11).

Timothy Liam Waters, “Materiality and Myth: Encountering the Broken Body in the Eddic Corpus,” Viking and Medieval Scandinavia 18 (2022): 179–206.

Bruce Holsinger, “Object-Oriented Mythography,” Minnesota Review 80 (2013): 128–29.

The medium of the piece is not actually wood, but the impression given by the linocut provides this sense.

I always learn so much from your work! the least of which is there are so many new words I need to look up and learn <3 A fabulous read as always

Great read!